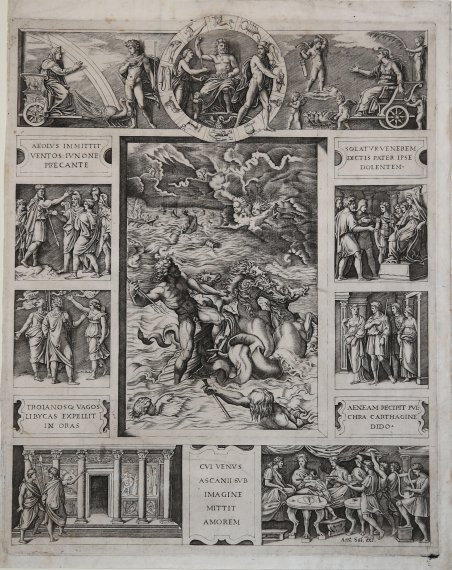

Quos Ego

Metodi di Pagamento

- PayPal

- Carta di Credito

- Bonifico Bancario

- Pubblica amministrazione

- Carta del Docente

Dettagli

- Anno di pubblicazione

- 1516

- Formato

- 333 X 420

- Incisori

- RAIMONDI Marcantonio

Descrizione

Bulino, circa 1516. Da un soggetto di Raffaello. Esemplare del secondo stato di tre con l’indirizzo del Salamanca. Bellissima prova, impressa su carta vergata coeva con filigrana “scudo con stella e lettera M”, con sottili margini, piccoli strappi restaurati nei margini, per il resto in ottimo stato di conservazione.La composizione illustra alcuni episodi tratti dal primo libro dell’Eneide. Derivata dalla celebre Tabula Iliaca Capitolina, ne rappresenta una contemporanea traduzione a stampa, espressamente richiesta da Raffaello a Raimondi, e da quest’ultimo eseguita, con ogni probabilità, nello stesso anno. Le scene, chiuse entro pannelli, sono riprodotte alla maniera dei rilievi antichi mentre il grande campo nel mezzo è concepito alla maniera di un quadro. La scena principale descrive le flotte troiane in balia di una tempesta, con Enea che alza le braccia al cielo in gesto implorante. In primo piano Nettuno, a cavallo della quadriga, placa le onde del mare pronunciando minaccioso le celebri parole “Quos ego!”. “[…]it ' presents subjects from Book One of the Aeneid, particularly those that take place after the escape of Aeneas and his men from Troy and before their departure from Carthage. The central scene of ' Quos Ego, and its eponymous subject, is that moment at the beginning of ' the poem when Neptune commandingly calms a storm in order to procure Aeneas’s passage to the shores of North Africa. The surrounding scenes represent the circumstances and the deeds that follow thereupon. On the upper left, we see Juno ordering Aeolus, god of the winds, to wreak havoc on the Trojan ships. In the central roundel, Venus implores the enthroned Jupiter to help her son, Aeneas, and the Trojans, with Mercury departing ' to deliver Jupiter’s help. On the upper right, Venus sends Cupid to lend additional support to Aeneas. On the left frame flanking ' the Neptune scene, we see Aeneas consoling the men who have survived the storm, Aeneas’s conversation with his mother, and, at the bottom left, ' Aeneas and Achates admiring paintings ' of the Trojan War on the walls of Juno’s temple in Carthage. In the small spaces to the ' right of the Neptune scene we see the Trojans in Dido’s throne room, then Dido leading Aeneas to a banquet, and at the bottom right, Dido, Aeneas, and Cupid, here dis-guised as Ascanius, dining together. It is during this feast that Dido falls in love with Aeneas by means of the wiles of Cupid, thus setting the stage for their tragic rupture. […] Quos Ego is only one in a group of prints by Raphael and Marcantonio ' that ' present ' episodes ' from ' the Aeneid, ' some of ' which are among the most famous in the Raphael–Marcantonio œuvre. […] Of course, the striking artificiality of the frame is further emphasized by Raphael’s adoption of all’antica style for its scenes and inscriptions. The scenes of the frame, after all, are portrayed according to the model of Antonine relief sculpture that Raphael was studying at this time in Rome. In the spirit of his precocious art historical researches, Raphael does not project his figurations into anything like believable, perspectivally correct settings, but rather places them, in the manner of Roman reliefs, among disproportionately small props standing for doorways and buildings. […] Yet, Raphael’s most brilliant all’antica gesture was to organize the whole print in accord with the example of the tabula iliaca, a type of classical stone carving that depicted Homeric and Virgilian episodes in compartments around a larger scene. By organizing his scenes according to this framework, Raphael not only emulated antique artistic example, but also took advantage of a structural homology between the sculptural tabula and the theoretical ideal of the window-like image. In this way, Raphael lent classical weight to a contemporary concept of painting, underlining that what we see through it looks like an actual view into profound depth: Neptune’s s. Engraving, about 1516. After Raphael. Example of the second state of three, showing the address of Antonio Salamanca. A very good impression, printed on contemporary laid paper with watermark "shield with star an letter M", with margins, some small tears repaired at the margins, otherwise in excellent condition. Ambitious in terms of the subject matter and the complex compositional conception in the style of classical relief sculptures, this print is considered among the most important ones of Marcantonio Raimondi’s prolific career and one of his most accomplished examples of “ancient engraving”. In fact, the composition of the scenes is inspired by a relief dating to the first century A.D. known as the Tabula iliaca, a tablet illustrating scenes from the Iliad and the Odyssey in a series of small narrative panels arranged around a central scene. “[…]it ' presents subjects from Book One of the Aeneid, particularly those that take place after the escape of Aeneas and his men from Troy and before their departure from Carthage. The central scene of ' Quos Ego, and its eponymous subject, is that moment at the beginning of ' the poem when Neptune commandingly calms a storm in order to procure Aeneas’s passage to the shores of North Africa. The surrounding scenes represent the circumstances and the deeds that follow thereupon. On the upper left, we see Juno ordering Aeolus, god of the winds, to wreak havoc on the Trojan ships. In the central roundel, Venus implores the enthroned Jupiter to help her son, Aeneas, and the Trojans, with Mercury departing ' to deliver Jupiter’s help. On the upper right, Venus sends Cupid to lend additional support to Aeneas. On the left frame flanking ' the Neptune scene, we see Aeneas consoling the men who have survived the storm, Aeneas’s conversation with his mother, and, at the bottom left, ' Aeneas and Achates admiring paintings ' of the Trojan War on the walls of Juno’s temple in Carthage. In the small spaces to the ' right of the Neptune scene we see the Trojans in Dido’s throne room, then Dido leading Aeneas to a banquet, and at the bottom right, Dido, Aeneas, and Cupid, here dis-guised as Ascanius, dining together. It is during this feast that Dido falls in love with Aeneas by means of the wiles of Cupid, thus setting the stage for their tragic rupture. […] Quos Ego is only one in a group of prints by Raphael and Marcantonio ' that ' present ' episodes ' from ' the Aeneid, ' some of ' which are among the most famous in the Raphael–Marcantonio œuvre. […] Of course, the striking artificiality of the frame is further emphasized by Raphael’s adoption of all’antica style for its scenes and inscriptions. The scenes of the frame, after all, are portrayed according to the model of Antonine relief sculpture that Raphael was studying at this time in Rome. In the spirit of his precocious art historical researches, Raphael does not project his figurations into anything like believable, perspectivally correct settings, but rather places them, in the manner of Roman reliefs, among disproportionately small props standing for doorways and buildings. […] Yet, Raphael’s most brilliant all’antica gesture was to organize the whole print in accord with the example of the tabula iliaca, a type of classical stone carving that depicted Homeric and Virgilian episodes in compartments around a larger scene. By organizing his scenes according to this framework, Raphael not only emulated antique artistic example, but also took advantage of a structural homology between the sculptural tabula and the theoretical ideal of the window-like image. In this way, Raphael lent classical weight to a contemporary concept of painting, underlining that what we see through it looks like an actual view into profound depth: Neptune’s sea is a realm of direct, sensate impressions. It is, in sum, a painting.” Christian Kleinbub, "Raphael's 'Quos Ego': Forgotten Document of the Renaissance 'Paragone', Word and . Cfr. Bartsch 352 II/III, Delaborde 102; Oberhuber, Roma e lo stile classico di Raffaello, p. 299.