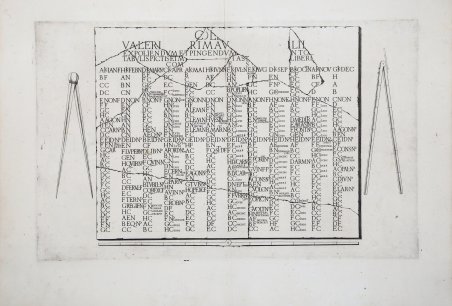

Bulino, 1550 circa, titolato, privo di data ed indicazioni editoriali. Raffigura una lastra marmorea di età augustea posseduta dalla famiglia Maffei. Esemplare nel primo stato di cinque per Alberti (primo di quattro per Rubach che non conosce la ristampa di Giovanni Orlandi), avanti l’imprint di Claudio Duchetti. Magnifica prova, ricca di toni, impressa su carta vergata coeva con filigrana “cappello cardinalizio (cfr. Woodward nn. 233-236), con margini, in perfetto stato di conservazione. “I cosiddetti «Fasti Maffeiani» vennero in possesso della famiglia Maffei nel 1547. Si tratta di una lastra marmorea di età augustea che tramandava il calendario giuliano e che, unitamente alle tavole pasquali incise sulla statua del cosiddetto Sant’Ippolito, furono fondamentali per la ricostruzione del calendario gregoriano. La tavola è oggi conservata a Roma, Musei Capitolini. Dell’incisione si conosce oggi una prima tiratura priva dell’indirizzo editoriale cui segue quella di Claude Duchet, replicata più tardi da H. Van Schoel e da Jacobo De Rubeis” cfr. Marigliani, ' Lo splendore di Roma nell’Arte incisoria del Cinquecento). L’opera appartiene allo ' Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae, la prima iconografia della Roma antica. La lastra figura nell'Indice del Lafreri al n. 223, descritta come ' Calendario antico nel Palazzo di Farnese. Lo ' Speculum ' ebbe origine nelle attività editoriali di Antonio Salamanca e Antonio Lafreri (Lafrery). Durante la loro carriera editoriale romana, i due editori - che hanno lavorato insieme tra il 1553 e il 1563 - hanno avviato la produzione di stampe di architettura, statuaria e vedutistica della città legate alla Roma antica e moderna. Le stampe potevano essere acquistate individualmente da turisti e collezionisti, ma venivano anche acquistate in gruppi più grandi che erano spesso legati insieme in un album. Nel 1573, Lafreri commissionò a questo scopo un frontespizio, dove compare per la prima volta il titolo Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae. Alla morte di Lafreri, due terzi delle lastre di rame esistenti andarono alla famiglia Duchetti (Claudio e Stefano), mentre un altro terzo fu distribuito tra diversi editori. Claudio Duchetti continuò l’attività editoriale, implementando le lastre dello Speculum con copie di quelle “perdute” nella divisione ereditaria, che fece incidere al milanese Amborgio Brambilla. Alla morte di Claudio (1585) le lastre furono cedute – dopo un breve periodo di pubblicazione degli eredi, in particolare nella figura di Giacomo Gherardi - a Giovanni Orlandi, che nel 1614 vendette la sua tipografia al fiammingo Hendrick van Schoel. Stefano Duchetti, al contrario, cedette le proprie matrici all’editore Paolo Graziani, che si associò con Pietro de Nobili; il fondo confluì nella tipografia De Rossi passando per le mani di editori come Marcello Clodio, Claudio Arbotti e Giovan Battista de Cavalleris. Il restante terzo di matrici della divisione Lafreri fu suddiviso e scisso tra diversi editori, in parte anche francesi: curioso vedere come alcune tavole vengano ristampate a Parigi da Francois Jollain alla metà del XVII secolo. Diverso percorso ebbero alcune lastre stampate da Antonio Salamanca nel suo primo periodo; attraverso il figlio Francesco, confluirono nella tipografia romana di Nicolas van Aelst. Altri editori che contribuirono allo Speculum furono i fratelli Michele e Francesco Tramezzino (autori di numerose lastre che confluirono in parte nella tipografia Lafreri), Tommaso Barlacchi, e Mario Cartaro, che fu l’esecutore testamentario del Lafreri, e stampò alcune lastre di derivazione. Per l’intaglio dei rami vennero chiamati a Roma e impiegati tutti i migliori incisori dell’epoca quali Nicola Beatrizet (Beatricetto), Enea Vico, Etienne Duperac, Ambrogio Brambilla e altri ancora. Questo marasma e intreccio di editori, incisori e mercanti, il proliferare di botteghe calcografiche ed artigiani ha contribuito a creare il mito. Engraving, ca. 1550, titled, lacking date and editorial indications. Depicts a marble slab from the Augustan age owned by the Maffei family. Example in the first state of five for Alberti (first of four for Rubach, who is unaware of Giovanni Orlandi's reprint), before Claudio Duchetti's imprint. Magnificent proof, rich in tone, printed on contemporary laid paper with "cardinal's hat" watermark (see Woodward nos. 233-236), with margins, in perfect condition. "The so-called "Maffeian Fasti" came into the possession of the Maffei family in 1547. This is a marble slab from the Augustan age that handed down the Julian calendar and which, together with the Easter tablets engraved on the statue of the so-called St. Hippolytus, were fundamental to the reconstruction of the Gregorian calendar. The panel is today preserved in Rome, Capitoline Museums” (translation from C. Marigliani, ' Lo splendore di Roma nell’Arte incisoria del Cinquecento). The work belongs to the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae, the earliest iconography of ancient Rome. The Speculum originated in the publishing activities of Antonio Salamanca and Antonio Lafreri (Lafrery). During their Roman publishing careers, the two editors-who worked together between 1553 and 1563-started the production of prints of architecture, statuary, and city views related to ancient and modern Rome. The prints could be purchased individually by tourists and collectors, but they were also purchased in larger groups that were often bound together in an album. In 1573, Lafreri commissioned a frontispiece for this purpose, where the title Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae appears for the first time. Upon Lafreri's death, two-thirds of the existing copperplates went to the Duchetti family (Claudio and Stefano), while another third was distributed among several publishers. Claudio Duchetti continued the publishing activity, implementing the Speculum plates with copies of those "lost" in the hereditary division, which he had engraved by the Milanese Amborgio Brambilla. Upon Claudio's death (1585) the plates were sold - after a brief period of publication by the heirs, particularly in the figure of Giacomo Gherardi - to Giovanni Orlandi, who in 1614 sold his printing house to the Flemish publisher Hendrick van Schoel. Stefano Duchetti, on the other hand, sold his own plates to the publisher Paolo Graziani, who partnered with Pietro de Nobili; the stock flowed into the De Rossi typography passing through the hands of publishers such as Marcello Clodio, Claudio Arbotti and Giovan Battista de Cavalleris. The remaining third of plates in the Lafreri division was divided and split among different publishers, some of them French: curious to see how some plates were reprinted in Paris by Francois Jollain in the mid-17th century. Different way had some plates printed by Antonio Salamanca in his early period; through his son Francesco, they goes to Nicolas van Aelst's. Other editors who contributed to the Speculum were the brothers Michele and Francesco Tramezzino (authors of numerous plates that flowed in part to the Lafreri printing house), Tommaso Barlacchi, and Mario Cartaro, who was the executor of Lafreri's will, and printed some derivative plates. All the best engravers of the time - such as Nicola Beatrizet (Beatricetto), Enea Vico, Etienne Duperac, Ambrogio Brambilla, and others ' - were called to Rome and employed for the intaglio of the works. All these publishers-engravers and merchants-the proliferation of intaglio workshops and artisans helped to create the myth of the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae, the oldest and most important iconography of Rome. The first scholar to attempt to systematically analyze the print production of 16th-century Roman printers was Christian Hülsen, with his Das Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae des Antonio Lafreri of 1921. In more recent times, very important have been the studies of Peter Parshall (2006) Alessia Alberti (2010), Birte Rubach and Cle. Cfr.

Scopri come utilizzare

Scopri come utilizzare