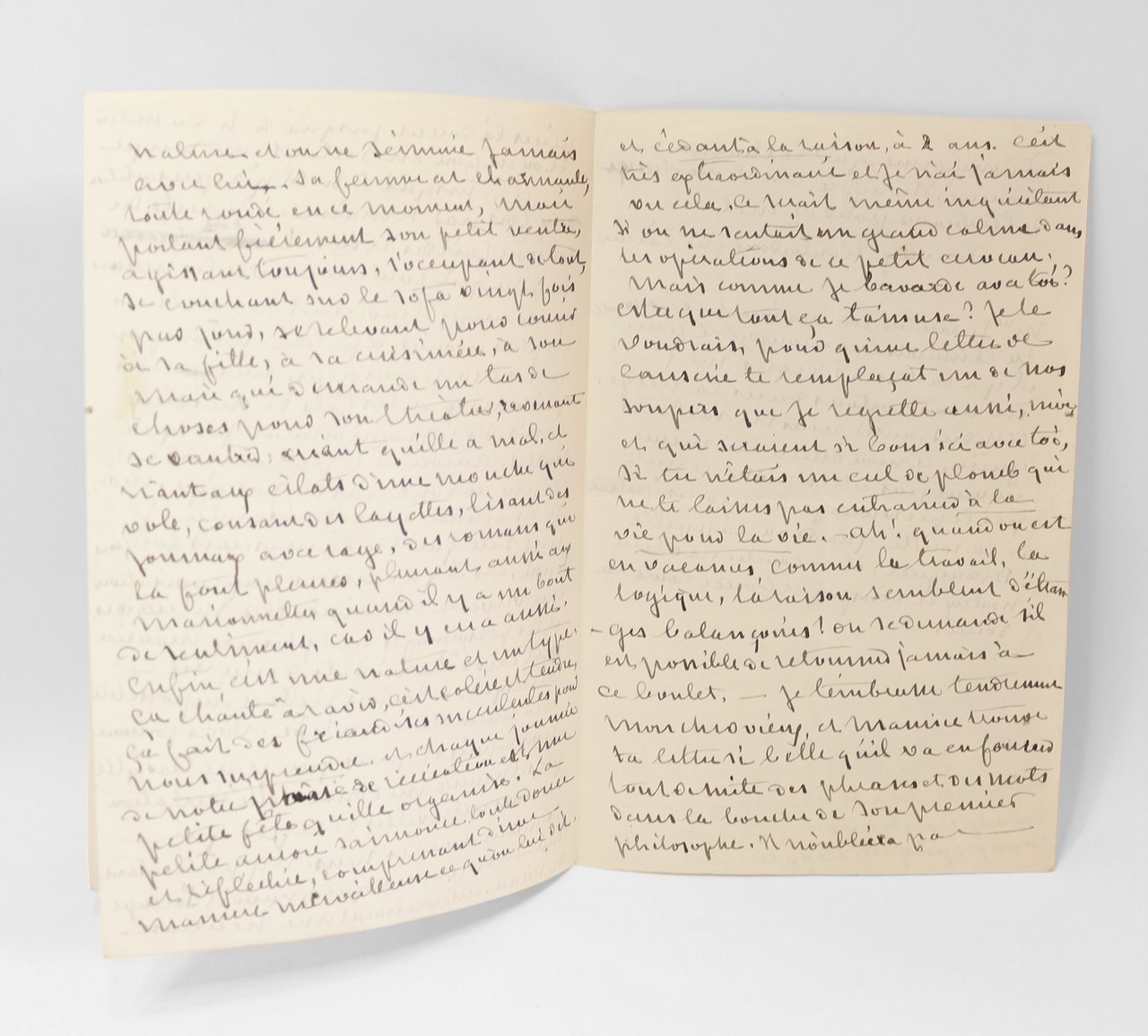

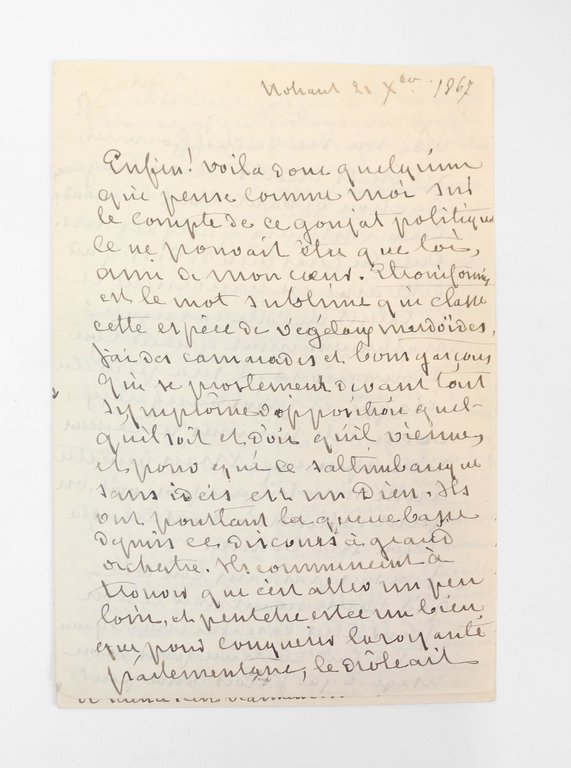

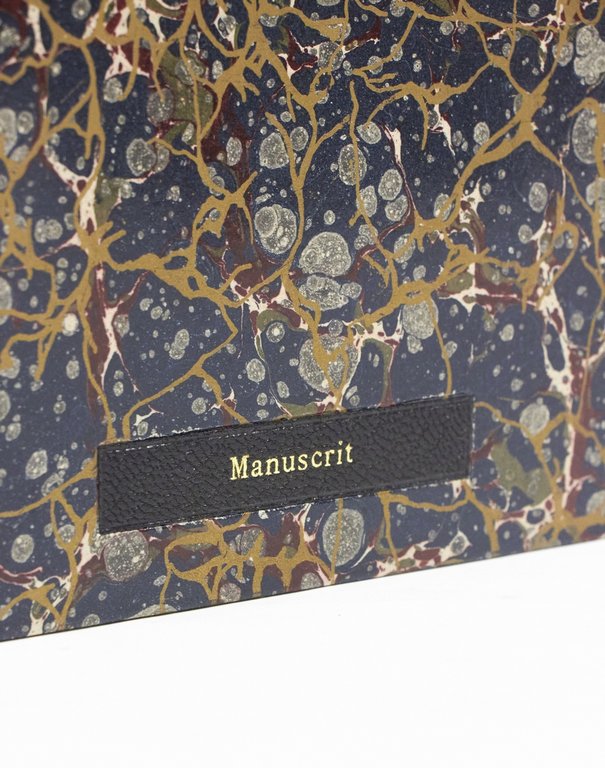

Nohant [Nohant-Vic] 21 décembre 1867 | 13.40 x 20.70 cm | deux feuillets sous chemise et étui | Autograph letter from George Sand to Gustave Flaubert dated December 21, 1867, 8 pages on two lined leaves. Published in Sand's Correspondance, XX, pp. 642-645. From one of the finest literary correspondences of the century, this letter written on Christmas Eve 1867 is a sublime testament to the frank friendship between George Sand, the “old troubadour”, and Gustave Flaubert, christened “cul de plomb” [leaden ass] after declining his invitation to Nohant to complete L'Éducation sentimentale. Despite their seventeen year-age gap, opposing temperaments and divergent outlooks on life, the reader is gripped by the tenderness and astonishing verve of George Sand's long confession to Flaubert. At the height of her literary fame and enjoying her theater in Nohant, Sand talks at length about politics, their separation, their conception of the writer's work, and life itself. In this “stream-of-consciousness” letter, Sand naturally and freely sets down on paper eight pages of conversations with Flaubert who made only too rare and brief appearances in Nohant: “But how I chat with you! Do you find all this amusing? I'd like a letter to replace one of our suppers, which I too miss, and which would be so good here with you, if you weren't a cul de plomb [leaden ass] who won't let yourself be dragged along, to life for life's sake”, whereas Flaubert's motto, then busy writing L'Éducation sentimentale, was rather art for art's sake. In the end of 1867, Sand grieved the death of an “almost brother”, François Rollinat, which Sand appeased with letters to Flaubert and lively evenings at Nohant: “This is how I've been living for the last 15 days since I stopped working [.] Ah'! [.] Ah! when you're on vacation, work, logic and reason seem like strange swings.” Sand was quick to criticize him for working tirelessly in his robe, “the enemy of freedom”, while she was running up and down mountains and valleys, from Cannes to Normandy, even to Flaubert's own home, which she had visited in September. On this occasion, Sand had happily reread Salammbô, where she picked up a few lines for her latest novel, Mademoiselle Merquem. Their literary and virile friendship, similar to Rollinat's, defied the old guard of literati who declared the existence of a “sincere affair” between man and woman utterly impossible. Sand, who has been described in turn as a lesbian, a nymphomaniac, and made famous for her resounding and varied love affairs, began a long and intense correspondence with Flaubert, for whom she was a mother and an old friend. She called herself in their letters “old troubadour” or “old horse” and no longer even considered herself a woman, but a quasi-man, recalling her youthful cross-dressing and formidable contempt for gender norms. To Flaubert had compared the female writers as Amazons denying their femininity: “To better shoot with the bow, they crushed their nipples”, Sand replied in this letter: “I don't share your idea that you have to do away with the breast to shoot with the bow. I have a completely opposite belief for my own use, which I think is good for many others, probably for the majority”. A warrior, yes, but a peaceful warrior, Sand willingly adopted the customs of a world of misogynistic intellectuals, while remaining true to herself: “I believe that the artist should live in one's nature as much as possible. To the man who loves struggle, war; to the man who loves women, love; to the old man who, like me, loves nature, travel and flowers, rocks, great landscapes, children too, family, everything that moves, everything that fights moral anemia,” she then adds. A fine evocation of her “green period”, this passage marks the time of Sand's country novels, when, mellowed by the years, she gave herself over entirely to contemplation to write François le Champi, La Mare au diable and La Petite Fadette. But her love of nature didn't stop

Scopri come utilizzare

Scopri come utilizzare